Hope, Pain, and Valour

On the day 15.1.71 N.C. Hoborg introduced a group of three beings into the Neverhood. They were a mismatched lot, one looking Neverhoodian, another a tall hoophead, and another something no one could quite place. Hoborg’s children gathered around to see. Who were they?

Hope

The first of the three beings, a red-skinned boy in white clothes, chose “Krevel” as his name. It was a good name. Krevel, also known as haematite, was a mineral common on the Neverhood. In this way and more, Krevel made an honest effort to fit into his new homeland. Not many noticed that if he changed into brown clothes and closed his eyes, he would look exactly like Klogg used to. Hoborg and Willie, who did notice, didn’t like to think about it.Several weeks after they arrived at the Neverhood, Krevel and his two brothers bore witness to their first weasel hunt. This tradition was tolerated by Hoborg, who wasn’t fond of its many dangers, because everybody else simply loved it. The trill of Willie’s old music box threading through the hushed Weasel Arena made Krevel jittery with anticipation, too. It was no less than a sacred ritual.

This time the hunt went as smoothly as you’d please. An impressive purple weasel broke through the wall of the Arena just next to the Mulberry Bush. It ate the lit dynamite doll enthusiastically, and then exploded just as enthusiastically. Everyone cheered as they scaled down the Arena walls to gather meat, which had been strewn far and wide.

Krevel hurried to help, too. He picked up a claw so large that he couldn’t see over it and tried to navigate toward the meat carts. Little wonder: he walked into the Mulberry Bush instead. When he saw its pale fruits overhead, he yelped and stumbled back. Mulberries frightened him witless! And that was understandable, since one of them had almost killed him. All he had done was take a small bite. Immediately he began burning up and bloating, even after he spit the fruit out. Fortunately Hoborg was near and his prompt aid stopped the harsh allergic reaction and saved Krevel’s life.

Krevel shuddered and took one more step back for safety measures.

“Are you okay?” a Hoodian came up to him. Kam… zik? Krevel couldn’t recall all the names properly yet. “Here, let me take this. Dayum, that’s heavy!” he exclaimed, stealing the claw away from Krevel. The red-skinned Hoodian blushed in embarrassment, intertwining his hands behind his back, looking around to see if anyone else had heard his panicked outcry.

It was then that it happened, something that would change Krevel’s life forever and come to define him so chiefly. From that first impression of awe, boundless curiosity followed, and then there was no way back.

To put it simply, at that moment Krevel noticed that he was standing next to a gigantic hole. It was dark and gaping, and a wisp of cold air was coming out of it. Its upper rim was so high up that a Hoodian could stand on Krevel’s shoulders and still he couldn’t reach the top. This was where the weasel had burst through the rock, Krevel realised. It hadn’t seemed this gargantuan from the wall tops. The beast could have doubtless swallowed a Hoodian whole. Where did it come from?, Krevel wondered. Surely it must have come from somewhere.

Carefully he approached the opening and peeked inside. It was dark in there, but Krevel’s eyesight adjusted quickly. In the hole, there was a tunnel leading deeper into the rock.

Krevel glanced back. He spotted his hoopheaded brother watching him with suspicion in his eyes. Giving him a grin, he said:

“Are you making sure that I won’t do anything stupid?” In spite of the careless tone, he was reassured to find his brother was keeping an eye on him. It was the hoophead, after all, who had raced to fetch Hoborg while Krevel was choking to death on a mulberry.

The Hoodian narrowed his eyes. “You might. Perhaps you do have an idiotic streak coming from our brother.”

Krevel smiled wider but his tone was scolding: “Don’t say he’s an idiot. He’s trying.”

“Bah!”

“Anyway, check this hole out. It seems to lead somewhere.”

The hoophead strode to stand beside him, looking deeply unsettled. He but glanced inside and turned pale. “Ugh. Not the place for me. Are you going inside? Yeah, I’d go with you, but my stomach’s turning just when I look in there.”

“It’s no sweat. I can make it alone. I won’t get lost.”

“Oh, I’m not worried about you getting lost. You remember all the places and all the names. No, I’m worried about you getting eaten by a weasel.”

“There’s… that,” Krevel had to admit. “My plan was to run for my life if anything went awry…”

“You never know how fast a weasel is,” the hoophead pointed out. Krevel noticed that he had turned his back on the tunnel so that he wouldn’t have to look at it. To be fair, he said to himself, I am facing away from the Mulberry Tree, too.

They had to go shortly after that, to attend the roasting ceremony. But the idea to investigate the tunnel never quite left Krevel. During the feast he carefully asked around and he learned that nobody actually knew where weasels came from. Nobody cared, really. Weasels only came out when Willie’s music box was played, so it was unimportant where they came from. What was important that upon hearing the tune, they would come, and upon not hearing it, they would not.

Now Krevel was grossly dissatisfied with this answer. He couldn’t understand how Hoborg’s children could be content simply knowing that things worked, and never try to find out how they worked. Krevel’s mind was always at work, figuring out things big and small, making sense of the world around him. It would be so interesting to find out where weasels came from! And so he set out the next day to investigate the hole in the wall. Naturally, after promising his hoopheaded brother that he would be careful and bring along some dynamite sticks and matches.

The opening seemed undisturbed. Krevel took a deep breath and, for the first time, he entered the dark underground. Damp walls slipped past him. When the tunnel started to bend, he looked around to glimpse the last splotch of light of the outside world. And then, he pressed on.

He quickly found that he could see even by the barest sliver of light. Around him, there was only stone. There was also silence. Krevel listened to the silence intently, trying to gauge if there was a weasel close by. Soon the sound of his own footsteps was so loud that it echoed through the corridors and came back to him, whispering. He took his boots off. He left them at the first intersection and chose the path to the right.

Here the ceiling came lower and lower until he had to get down on his knees and crawl. He saw a trickle of water beside him, flowing somewhere away from him. Well, if the water could pass, so could he, he told himself as he came down on his belly and crawled forward on his elbows, kicking with his feet to propel himself.

And the stream did, indeed, go somewhere.

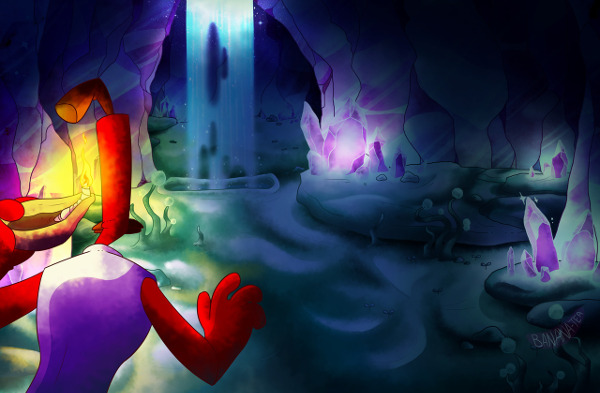

Krevel got to his feet and looked around, wide-eyed. He had reached a cave tall enough to stand and make a few paces. Light was scarce here, but still he thought he could see the walls glint.

He remembered that he had brought an oil lamp. He took it out of his chest compartment and lit it, shielding his eyes against the sudden brightness.

(Picture by Banana-Teatime.)

Krevel could feel his heart pound with excitement as he shuffled closer to investigate. The warm light reflected and refracted in a million ways at a million angles. It sparkled and gleamed, shone and danced. The surface washed by water was smooth enough that Krevel could see his reflection in it, perfect as a mirror. A little to the right the wall bent and undulated and his image became warped: head too large, one arm bigger than the other, the shadow Krevel bouncing funnily at the smallest movement from the real one.

The Neverhoodian giggled. It was so beautiful! How come there was a place like this on the Neverhood and nobody knew of it?

When Krevel got enough of the Mirage Cave (that was what he decided to call it), he headed back. He had to tell his brothers! He wanted to show the place to the entire Neverhood! Oh, how popular that would make him.

As he crawled back through the way he had come, his excitement abated a little. Elbows chafed and clothes soaked with cold water, he realised that he could never show this wonder to his claustrophobia-stricken brother. The hoophead couldn’t ever survive the crawling part, he would suffocate with terror.

Krevel found his boots at the intersection and he pulled them on. He had to shield his eyes against the blare of light as he walked toward the exit.

Outside he met Hoborg.

“Krevel?” the king exclaimed in plain surprise. “What were you doing in there?”

“Hoborg!” The Hoodian grinned wide with excitement. “Come with me, I must show you something!”

Skipping giddily, Krevel presented his discovery to his king. Hoborg followed him into the darkness and crawled through the narrow passage without a word of complaint. He was properly amazed at the Mirage Room, saying “ohh” and “wooow” at all the right moments. When they emerged again, however, he sobered up.

“Krevel,” he told his subject grimly, “you don’t know how lucky you were. Your first luck was, of course, that you made such an amazing discovery. And your second luck...” he shook his head. “...was that you came out when you did, because I was just about to seal that hole.”

Krevel stared at him for a second. “I would have been stuck inside,” he said softly. Then his brow scrunched up in confusion. Rubbing at his temple, he thought hard for a moment. Finally he gestured toward the hole. “Hoborg,” he said, “I – I couldn’t believe my luck when I found the Mirage Room. The odds that a piece of the Neverhood would be undiscovered after all this time… I thought…” I thought it made me special. “But you wanted to seal the hole, so that nobody could get inside. Was I… not supposed to find it? Is it a secret?”

Painfully, Krevel realised that there was no way Hoborg didn’t know about the Mirage Room. He had made the Neverhood. If he had intended to bar the access to the underground to his children, and Krevel had slipped in despite that… then punishment was coming for him.

But Hoborg’s reaction surprised him. “I...” The king scratched the side of his head. He wasn’t angry. He was… embarrassed? “I probably shouldn’t say this as the all-knowing creator of the place… but I didn’t know about the Mirage Room either. Up until now I had no idea there were tunnels in the walls. Back in the day I created them solid. I haven’t given them much attention since then. Whenever a weasel came up,” he shrugged, “I just sealed the hole and I was on my way again.”

Krevel stared at him. Hoborg shifted uncomfortably. Krevel blushed and looked away.

“I’m… sorry?” he said, unable to think of anything better. Then… the weasels must have come from the tunnels. And nobody had discovered this because Hoborg always cleaned up the rubble before anyone investigated what lay behind it.

“Oh, don’t be,” Hoborg replied in haste. “If anything, you should be proud! The Mirage Room was a great discovery. I would…” he looked toward the opening, “yes, I would love to visit it again! It is most extraordinary that something that beautiful exists in my world without my knowledge. I should definitely look into it. In fact...” He gave Krevel a wink. (At least, the Hoodian had a strong impression that it was a wink.) “How about we look into it together?”

Krevel’s jaw dropped. “I would love that!” he managed to say finally. He had been told that Hoborg’s time was precious – everybody wanted him to take part in their games and adventures, but the king couldn’t be everywhere at once. So being offered such an opportunity… well, it made Krevel tingly with feeling special all over again.

“Swell,” Hoborg laughed and patted the boy on the back. “First thing’s first, though. I need to seal this hole. Don’t worry,” he added at once, “it won’t be for good. Just watch.”

The king of the Neverhood took a deep breath. He set his shoulders back. Amiably he beckoned to the hole and the surrounding rubble flew up, melting and moulding until there was only smooth wall. “Here,” Hoborg said, smiling. He reached out and took what Krevel realised was a hidden lever into his hand. He pushed it up. A door opened up in the wall. “That should do it. Do you see where the lever is? Here, try to pull it. From a distance all you can see is a wall. The door can only be opened if you know where to find the lever.”

Krevel nodded, etching the location of the secret lever into his memory. Hoborg then looked inside the hallway, tapping his chin. “I wonder,” he said finally. “Behind the first corner I couldn’t see at all. Maybe I should install electric lighting in there.”

Krevel shrugged. For him a lamp was more than sufficient, but he presumed that other Hoodians would need stronger lighting so that they wouldn’t bump into walls and get lost. “It’s a good idea to install some lights.”

“Yes…” Hoborg drawled. “The problem is, I’m not very able with electricity. My brother, Ottoborg, he’s all about these electronic trinkets. But I’m better with stone and earth. Quater knows how far the tunnels go. It would take me weeks to get them fully lit.”

Krevel found that he was mildly disturbed by the idea of the hallways being illuminated by light bulbs upon kilometres of wires. He had sort of liked the darkness. It felt… private. Safe. In spite of the possible presence of weasels, which was strange now that he thought about it. From what did he feel safe in the darkness? “Then,” he suggested, “why don’t you just create a few lamps for starters? Let everyone bring their own when they go inside. We can store them here, at the entrance to the underground, together with an oil barrel. Plus, uh, maybe some tools? Shovels, pickaxes, that sort of stuff? If we ever needed to clear some rubble. Oh, and dynamite. Against weasels. In fact,” Krevel rubbed his lips, peeking inside, “it might be worth it to make a second door. Just in case another weasel runs up here. Opening the outside door and seeing a hungry weasel right in front of you…”

“Yes,” Hoborg cut in, a little nauseated, “that is a very good idea, Krevel.”

Together they worked out plans for the room. A few Hoodians flocked by, saw the two discussing something above a sheet of paper, and immediately Krevel’s discovery was the topic of the day. Hoborg created a small barrel of oil and a dozen lamps, while Krevel made an excursion to the Mirage Room every half an hour. The designing took much longer than originally anticipated because every Hoodian privy to the plan had something to add. On the other hand, consequently the room obtained many more features than just a shelf for lamps and a rack for mining tools.

Before dusk, it was done.

Now usually I don’t take to describing places. I will, however, describe this room, which later received the name Entrance Room, and even later Krevel’s Room. So many events of the Triplets’ lives took place here, it deserves to be recorded in all of its elegant utility.

The door to the room was, as said earlier, made of stone. It copied the surrounding rock so well that one might have overlooked it from afar. But up close, you did notice a small lever, which opened the door in a wide outward arc.

The room was seven by ten steps large, a puffed bubble in the rock with its curving high ceiling and rounded walls. When you entered, by your left hand there was a bed with soft sheets. It was big enough for two if they didn’t sprawl too much, and queen-sized for one. Every Hoodian tried it, and loved how it caressed the skin. They swore that they would take turns sleeping in that bed that Hoborg made for them, and it made Krevel smile.

Opposite the bed, to your right hand when you entered, there was a large desk and a stool that you could spin on. On the desk there was a pencil stand and a few large sheets of paper. For maps, Hoborg said. Above the desk there were shelves with lamps and dynamite sticks. Here, Hoborg said, they would store smaller the equipment for diving into the underground. On the desk, they would draw maps and show each other places where they’ve been. And when they’ve found something interesting and precious, they could examine it here under a lamp’s soft light.

Now, come. Step further into the room, one, two, three. The ceiling is lifting above you, and when you look up you notice that there are sparkles in it. Small freckles of multifaceted glass that reflect any light in the room. Stars, Krevel’s hoopheaded brother had called them. Quater knew where he had got the notion of stars, since there were none on the Neverhood’s night sky. But the hoophead said that if there were stars above his head, he wouldn’t mind coming into this room. And so Hoborg obliged, and there were shimmering stars overhead.

Five paces into the room, you stood in its centre. To your left, at the feet of the bed, there was a large chest. This was for storing maps, shovels and pickaxes, Hoborg said, plus anything that they brought from the underground and didn’t want to display. Because oh, then there were the displays. Lit from the inside by bands of glowing phosphorus, the display cases were built into the wall. There was a whole variety of sizes, depths: some at eye level were as big as a fist, some were so small you couldn’t fit a finger inside them. Some, near the ground, were large enough for a slim Hoodian to crouch in, and you had to wonder what kind of amazing thing would fill them one day. Because the showcases, they were all meant to be filled and marvelled at.

At the back of the room, there was another door. This one had a handle, and a spyglass. You could check the corridor behind it through the spyglass, to make sure no hungry weasel was hanging around. This door was special. Hoborg claimed that a weasel who heard the music box playing would sooner bash its head to mush before he broke through this door. Everyone believed him.

By this door, Krevel promised everyone that on the following day, he would take them inside to see the Mirage Cave again. And who knew, he said, maybe there were more such wonders waiting to be discovered. Tomorrow was another day. They all had something to look forward to.

Let’s leave Krevel’s story now. It is time to move on. Let’s meet his hoopheaded brother.

Pain

The second being that came to the Neverhood on 15.1.71 N.C. was a tall hoophead. And when I say tall, I do mean tall. Everybody had to tilt their heads back to look him in the eye. The hoophead had a habit of glowering from that height every time something upset him. Since there were a lot of things that upset him, he glowered all the time. And so Neverhoodians, in a good-hearted joke, tried to name him Kain, after a man who murdered his own brother. The hoophead took this name in a fit of prideful defiance, reversed it, and called himself Nike.Unlike Krevel, Nike didn’t like the Neverhood. He called it a golden cage, a place to trap him forever. When asked to explain, he would mutter: “There is nowhere to run,” and this summed it up both figuratively and literally.

The moment Nike learned that the Neverhood had been designed to last forever without death, he had extrapolated to the correct conclusion – that this would mean living with the same bunch of people forever. And not only would the people remain the same, the world would remain the same, too. There would never be anything truly new. Everybody would just live in the same old loop without any chance of escape.

The entrapment was all the stronger for how small the world was. Using all the conventional means, Nike could get from any place to another within fifteen minutes by the way of strutting. He wanted to run. He wanted to be free. But if he ran in any direction on the Neverhood, sooner or later he would hit a wall or fall off.

All of this wouldn’t be such a terrible problem, only if Nike was allowed to leave. After all, he and his brothers had come on Hoborg’s invitation. They could just leave and be on their way again, right? By the time Nike realised that they could no longer leave, it was too late. His two brothers loved the place, and every time he suggested the topic of leaving the Neverhood, he would get such death glares that the futility made him shut up. He was in the minority.

A few weeks into their stay, Krevel found the Neverhood underground, and Nike realised something unsettling.

Hoodians weren’t ill-willed, on the contrary, they were kind and forgiving. But they had a way about them, this collective mind, these quietly shared beliefs that nothing could shake. The truth of the universe was written on the Wall of Records. Hoborg was wiser than anybody. Leaving the Neverhood meant literally dying on the spot. (That’s what the drain said, after all!) Nike spent the first few weeks explaining to people that they were wrong, but he gave up when the truth dawned on him. It was him who was wrong. He couldn’t change them. He couldn’t tell them otherwise when they narrowed their eyes on him: “It’s him, Kain, who has a death wish. Keep away from him.”

It was all the more bitter that the Hoodians were willing to give Nike twenty more chances. “Accept our homeland, and we will accept you,” someone had told him with an encouraging smile. They bore no ill will, no, they were simply fundamentally different. They could not understand Nike’s desire to leave just as Nike couldn’t will himself to stay. The resulting stalemate was suffocating for both sides. Nike wanted to get out, to escape, but this was the very thing denied to him. He could never leave the home he was brought to.

The Neverhood swallowed him up and became his golden cage. And so the slowly burning hell started.

It took a few years before the situation got truly serious. Nike had his brothers to thank for the delay. They did their best to calm him, they conducted adventures with him, they climbed up to the roof of Willie’s house every time Nike wished to be at his favourite place, away from people and close to the sky. But it wasn’t enough. Gradually the hoophead began falling apart under the never-ending stress.

Claustrophobia is a peculiar thing. A few Hoodians had been created with chronic fears in their mind: some disliked heights, some couldn’t stand the sight of weasel bowels, some were irrationally afraid to hurt themselves. But no one’s phobia developed like Nike’s terrible, paralysing fear of enclosed spaces.

Nike never followed Krevel into the underground. He would occasionally sit in the Entrance Room, dousing all lamps and watching the gem-stars glitter in the phosphorus glow. But even those moments of contemplation grew rare by the second year. Originally Nike was fine with entering buildings, even the Hall of Records which seemed to go on forever. But gradually he grew loathe not to see the sky above him. He refined his own routes around the Neverhood, scaling walls and climbing over buildings, just so that he wouldn’t feel the ceiling pressing the air out of him. And things yet had to get worse.

On one evening, Krevel came back from exploring the tunnels of the Neverhood to find Nike sobbing in the Entrance Room. He set his lamp down, unstrapped the pickaxe on his back, and returned a few dynamite sticks into their drawer, stalling for time. Then he sat on the bed next to his brother.

“What’s wrong?”

Nike didn’t reply for a moment. He gazed up at the starry ceiling through his tears. If he narrowed his eyes a little, he could pretend that it was a sky full of different worlds. Worlds that he could go to. Worlds that would let him leave again, freely. But it was a lie. And Nike hated, hated lies.

“What’s wrong?” he repeated hoarsely. “Everything.” His voice was breaking. It sounded bone-weary, stretched thin. Nike liked how it expressed the entirety of him, just in three words. At least his voice was truthful. “This is my home and I hate my home. Hoborg takes care of us and I hate Hoborg. I think I’m even beginning to hate you for not feeling the same pain.” He couldn’t tear his eyes away from the stars. The lie was so alluring. But it was a lie and the reality was… “There is nowhere to run.”

Krevel scooted closer and hugged him. “It’s going to be fine,” he mumbled.

Nike sobbed harshly and he shook his head in disagreement. “Brother, you don’t understand me. It isn’t going to be fine. Not anymore. You know… the other day...” His throat was tight. His head hurt. It hurt so much that he would rather cut it off. Now where had he heard that? “I thought about the drain. How it says… that you will die if you jump down there.” As he heard himself saying that, his mind dissolved into a haze. His reality receded. His thoughts darted around. He tried to grasp for reality, for the truth amidst all the lies. You can go on. Things will get better. You’ll get used to this. They were the lies he had been telling to himself. He just wanted to escape from the pain bearing down on him from all sides. He had been lying to himself for that. He had been rejecting his self, and his self was just about to burst out of him in a spray of tears.

When he found the truth and realised what it was, he was chilled to the core. Sobbing nearly overcame him. Was this really what he had come to? All that was left of the proud hoophead?

Yes. It was all. It was the end. “I am going to jump,” he said in sudden clarity.

Krevel, who had been rocking him until then, stilled. Voice quivering and pale, he whispered: “What?”

But Nike wasn’t there to answer him anymore.

In and out of the great big loop of pain. Sometimes it was required of Nike to speak. He tried his best to oblige. But his steady world had turned into a frenzy, a whirlpool of lies, an orgy of fantasies. He had lost himself. He just tried to hold on to the knowledge that it would end soon.

He was in the Castle. Hoborg was asking something. Nike heard the word “breakdown”. He was clutching at his chest. He couldn’t breathe, he couldn’t take the tiniest breath. The walls were pushing all air out of his lungs. Quater, he was so scared.

Another moment, much later. Orange lamp light fluttering. Planning to sneak out and jump into the drain. Just wait until his brother fall asleep. It was terrible to have them watching him.

Some time after that, Nike fell asleep. And in his exhausted sleep, a friend came to him.

Even centuries later, Nike could recall the dream down to the smallest detail. It was a very happy dream. A relief from all the pain.

In the dream, he was standing on a plain that stretched out so far that he couldn’t see its edges. The plain was him, the truth of him. Knowing this, he loved it. He walked on it, he jogged on it, he raced toward the mountains on the horizon. That is how life should be, he thought to himself. Free.

Then a friend came to him. It wasn’t one of his brothers, though, it was someone else. Looking at him, Nike thought that it was Quater. An almighty being. A shimmering entity. One that could make anything happen.

“Are you happy?” the friend asked him.

Nike laughed in surprise. “Of course I am!” he exclaimed. “I am with myself. There is no place where I’d rather be. Look,” he pointed toward the mountains on the horizon, “do you see those twin peaks? They are my brothers. They are with me, watching over me. Always.”

The friend nodded and changed his question a little. “Are you happy on the Neverhood?”

Nike blinked. The Neverhood…

Lightning and thunder tore through the sky. Rocks sprang into the air around Nike. They flew at him, battered him, crushed him, buried him. The Neverhood. The place where Nike could never live.

The scene stilled. The friend was watching in horror. The stones had piled on top of Nike’s body, a raised grave.

“The Neverhood is my tomb,” Nike replied, voice barely a whisper through his destroyed lungs and throat. “I will die there, and it will happen soon. Then all of this will become irrelevant.”

“No!” the friend shouted. The force of his voice blew the rocks away from Nike. It vibrated to the core of him. Such power. “You will not die. I will not allow you to die.”

“But,” the hoophead shrugged helplessly, “the Neverhood is my tomb.” He gestured around him. “My world isn’t a tomb. It can never be a tomb. It is a plane, wide and hard and free.”

The friend looked at him with fierce eyes. Nike felt his layers be blown away under that gaze. He waited until his core was revealed, and he wasn’t surprised that it had the shape of his world. The up and down of the infinite plain were good and evil. Aboard it he walked, never losing sight of his brothers. Nothing more was needed. The clear air obstructed nothing from his view. Everything was clear, rigid, and unchanging.

The friend firmly grasped Nike’s shoulder.

“What if you changed?” he asked.

There, the dream ended.

When Nike woke up, he felt better. There was still some pain under his thoughts, but mostly he was just numb. His brothers were happy that he was talking to them, although they did say that he was strangely aloof. After breakfast, Nike asked them to let him think. They did not have to leave, in fact, it was very comforting to have them there. Nike just asked them not to talk. He needed the space and all the time of the day to digest the friend’s question.

What if he could change? Does staying true to oneself mean one cannot change? No, Nike reasoned. One can stay true to oneself throughout changes. One can embrace change, welcome it, let it do its work upon him and watch closely. No, it is not a bad thing to change.

He wished that he could change then. The way he was, his only truth was that he would take his own life as soon as he was allowed to. If he changed, so would his truth. He could stay. Hell, maybe he could even come to like the Neverhood a little! Maybe he could survive. He would lose what he used to be forever, but he wouldn’t lose his life and he wouldn’t lose his brothers.

He wanted to change so much.

After they ate dinner, he became scared. Holding his brothers’ hands, he made them swear not to leave as he slept. He was tired, but he didn’t want to go yet. “I’m afraid that after I wake up, it won’t be me,” he told them.

“Even if it’s not you, we’ll love you all the same,” they told him.

If you wish for something very hard, it will happen. That is what Nike thought when he saw Quater coming to him again on the following night. It was a joyous reunion.

“You can make me change, can’t you?” Nike said eagerly, taking his friend’s hands.

“I can,” the friend admitted reluctantly. “But it is not right. You are you. You have a right to live as you are.”

Nike shook his head, grinning. “Who I am already decided to die. This wide plain,” he gestured around him, “is ready to fall apart to make way for something new. In some way, it will still be me. In some way, I will die.” He felt peace in his heart. The end had finally, finally come for him. “Please, do it. You have the power. Change me. Release me. Set me free of myself.”

After that the dream became chaotic. It hurt at places, it was agony at others, it was peaceful at some and very sad elsewhere. It was a deep, deep pain, combined with a deep, deep numbness. It was the feeling of dying. It was the feeling of being born.

Of the following days, Nike kept few memories. Krevel’s green eyes boring into him, questions and disturbance in them. Confused stares, reason unknown.

Every night, Nike died and was reborn as someone a little different. His inner world changed with him. It became undulated, then even hilly. It was still a land under a starry sky, but now there were bushes here and there, even houses. The night the first tree grew, Nike marvelled at it for hours. He felt so happy for it, so happy with it.

And then it was done.

Nike lay awake in his bed, looking at the ceiling. It was just a ceiling. An ordinary, green and violet ceiling. It was a wall. There was air on the other side of it. There was air and space all around him.

He looked to the side. His brothers were sleeping there. He could hear them breathing. Drawing in the clean air of the Neverhood.

Nike thought, maybe he should be confused. Maybe he shouldn’t feel that way. But he didn’t know why anymore. He had changed, and he didn’t understand the guy who was before it. He had lost him forever.

Very silently Nike crept out of the bed. He probed himself. Everything was clear. Nothing was hazed, nothing was askew. There was no pain, only the memory of it.

He looked out of the window, and saw the Neverhood.

He gazed there for a long time. He stood, and gazed. It was hard to come to terms with the thought that, maybe, it was going to be nice to live here.

Valour

Now let me tell my final story, about the third brother. It will not be as hopeful as Krevel’s story, nor as painful as Nike’s story. It will be about bravery. And it will be about fear.The third being who came to the Neverhood on 15.1.71 N.C. was something that no one could quite place. His skin was a dim shade of orange and from his head grew an exceptionally long stem. The stem was, quite truthfully, hilarious. The being constantly played with it and pulled at it, delivering gestures and emotions of clarity and variety hitherto unseen. This was good because this guy had two problems, which no Hoodian quite knew how to deal with. One, he could not speak the common tongue, and instead used some burring gibberish. And two, he tried to steal Hoborg’s crown on his first day. Needless to say, the second was worse.

To the being’s credit, let me say that he had no idea what a taboo he was breaking. He was a soul who loved attention, who wanted nothing more than to have a crowd look at him. But not with such eyes as they did when the crown was finally wrangled out of his hands. Those eyes were full of contempt and fear, and the being was overcome with such feeling of loneliness that he would have done anything to make it up to them.

He chose his name then, Nehmen Aber Zurückgeben. It meant “take but return” in his mother tongue and it was supposed to always remind everyone that he had not meant to take the crown for himself. Sadly, the name was too long and people just called him Nehmen (with terrible pronunciation, too), “take”, which beat the purpose. Fortunately everyone soon forgot what it meant.

That left only the first problem: that Nehmen couldn’t understand what everyone was saying, and vice versa. Pantomime helped, sketching helped, but the boy was unable to communicate any of the finer points, like the texture of a mulberry or the weird sad smile of that dark-haired girl. That was when the box came into play.

Though Nehmen had no idea how, the box was able to translate anything he said into the common tongue. He suspected that the translations weren’t very accurate, but it was definitely a step up compared to pantomime. The annoying thing was that the box took its sweet time translating. Nehmen had to make awkward pauses in his speech, otherwise it would start speaking over him. Others almost never waited (except for Krevel, who always waited) so Nehmen lost half of what they said. It was frustrating. But it was the best he had.

He used the box every day. He carried it around since it was too big to fit into his chest compartment. He always set it next to him and let it speak with him. Sometimes he forgot to bring the box, and he panicked a little every time he realised he didn’t have it. He wouldn’t find peace until he found the damned thing again.

And then… ack. Every time Nehmen thought of it, he had to grimace and sigh. Then there was the other thing. The thing Nike had said on the very first day of their lives, even before they arrived at the Neverhood: “You need to learn the common tongue.”

Nehmen hated the lessons. Disliked them. Avoided them. Learning grammar, cramming vocabulary, who would ever prefer that to the lovely convenience of the box?

One day Krevel tried to drag him into the Entrance Room (which was, slowly but surely, being called Krevel’s room more and more often) to teach him some more English. Even though there was no party on that day – or perhaps because of it! - Nehmen ended up annoying his brother more than usual. Krevel took it patiently, but even he had a breaking point, as Nehmen had already learned several times. This time, it was no less startling.

“Well then, screw you!” Krevel yelped, throwing his pen into the corner. “Are you seriously so dumb? We’ve been over this four times, and you still don’t remember a thing!”

The thing he was talking about was quite basic. “I was, you were, he was.” Facing the usually gentle Krevel’s anger, Nehmen had to admit that he would learn it and remember it easily – if only he cared. And he didn’t. And his brother had no right to speak to him this way!

“Maybe you’re the dumb one,” he riposted and stuck his tongue out. “Your teaching suuuucks!” He was dismayed when the box failed to pick up on the last word, but Krevel had surely got the meaning.

“Yeah, maybe it does!” Sitting back and crossing his arms, he sulked as the box’s translation played out. “I don’t know why I still bother. You’re never going to learn this.”

Nehmen grimaced in guilt. It wasn’t often that Krevel gave in to helplessness. At least not publicly. But he saw his chance, and he took it.

“You’re completely right,” he nodded solemnly. “I’m never gonna learn. Give up now, before you waste any more effort.”

Krevel stared at him.

Krevel kept staring at him.

Nehmen had the uncomfortable feeling that Krevel’s eyes bore through him. He shifted and made a fake grin.

Krevel got up. “You’re right,” he said, tucking their notebook into his chest compartment and retrieving the pen from the corner. “I’m giving up on you. No more lessons. You’re free.”

Nehmen whooped in joy. “At last! Thank you!” he shook his brother’s hand. Krevel grunted something that the box failed to translate, and exited through the back door, into the underground.

“Hey, you forgot to take a lamp!” Nehmen shouted after him in good spirits. The box repeated it quietly, distinctly, without emotion. Krevel didn’t hear it. “Tee hee,” Nehmen giggled and headed out, wondering if he could throw a party because the annoying lessons were over. No reason too silly, right?

Well, it turned out that this reason wasn’t silly, but rather… not shared by the Hoodians that Nehmen had called friends. They weren’t overjoyed as he was, but annoyed. They refused to throw a party, and one or two even told Nehmen that it wasn’t cool to send his bro away like that. For the first time Nehmen saw clearly what a double-faced game they had been playing. On one hand, they nodded their heads in sympathy when he described how boring and pointless the lessons were. But secretly they were glad that someone else felt responsible for teaching him their language. They were happy because it didn’t have to be them to teach him.

Needless to say, Nehmen walked away from his “friends” in a sour mood.

He stalked around the Neverhood, kicking up stones and glaring angrily. News travelled fast. Soon he found that he heard his and Krevel’s name brought up in foreign conversations. He noted how shameless the Hoodians were. They relied on the fact that he knew no English, and so they could discuss anything in front of him as long as the box couldn’t hear them. When they saw Nehmen approaching with the box, they’d switch to whispering. As he passed, they eyed the box warily, careful for any signs that it picked up their gossip.

Nehmen hated it. Out of sheer spite, he left the box under the Mulberry Bush (he knew he could always find it there) and he ventured out into the Neverhood without its aid. He could still hear Krevel’s name mentioned here and there. Apparently their falling out was the topic of the day! When Hoodians saw him approach, their eyes searched for the box. When they saw he didn’t have it, they shrugged and continued gossiping loudly as if he wasn’t there.

As if he wasn’t there. Nehmen turned that phrase over in his mind, and he found it disgustingly true. He was no better than air to them! The box made him everything he was.

The box… he grew nervous. He didn’t have it on him. He would need it. He needed it.

He procured the box. Holding it in his hands made him feel safe. It was okay. Krevel was angry with him, but he never stayed angry for too long. Nehmen gave him a week at maximum, then he’d come crawling out of the underground and ask for forgiveness. Which Nehmen would happily grant him, but he wouldn’t allow any more English lessons. Those were over for good.

Nehmen smiled as he set out to find his friends and make up with them.

His guess was correct. Krevel emerged from his “geological survey” five days later, showing off a pretty row of crystals to anyone who cared to look. Nehmen stole two of them for good measure. Then he produced a hammer he had been holding onto for weeks, swearing by all his mysterious parents that he had found it under the Mulberry Bush. It was, of course, Krevel’s favourite hammer, so he would have never taken it on purpose!

Krevel did not believe a word, Nehmen’s acute people-sense told him, but he accepted the hammer nevertheless and thanked Nehmen for returning the find. He addressed him with his full name, Nehmen Aber Zurückgeben, and Nehmen realised gladly that not only did Krevel get the meaning of his name, his accent was also mellowing out! Maybe the guy could learn German instead! He told this to his brother immediately. His excitement was met with a sad, aloof smile. Nehmen did not like it, but he did note that Krevel didn’t refuse right away.

Several days later, out of the blue, a terrible tragedy occurred. To some it might seem trivial, but it was an event that changed Nehmen’s life forever.

The box stopped working. No matter how Nehmen shook it, how he tuned it, no matter how he shouted at it – it remained silent. In tears, Nehmen took it to Klaymen, who had lent him the box. His peril was obvious. Klaymen nodded gravely and pointed at the sky. He traced a circle with his palms and said: “Idznak. Hoo, hoo, humph,” he demonstrated a Skullmonkey. “Beeep,” he pointed upward with his index finger and put it to the side of his head. “Jerry-O,” he said. He took the box, examined it, shook it. He tucked it under his armpit, gave Nehmen a big thumbs-up, and began walking away.

Nehmen understood that the box was being taken to repairs. But he felt so lonely, watching it peeking from under Klaymen’s arm. He shuddered. Quater, he hoped that the box would return to him soon. After all, he was nothing without it, less than air. It was all that he meant to his friends. Without the box… without the box…

A couple of hours later, Nehmen’s body was shivering uncontrollably. He felt terrible. He felt in pain, if that was a state a Hoodian could achieve. He had tried talking to his friends, he had tried to play a game – he couldn’t. He couldn’t tell stories without the box, he couldn’t brag, he was nothing, he was air, he was dead. He needed the box. He was crying, but it didn’t help.

His friends didn’t know what to do with him. They took him to Hoborg, but he didn’t know what to do with him. Nehmen’s two brothers stood above him, and they didn’t know what to do with him.

Nehmen traced a square in the air before him. He hugged that square with both hands, cuddling up to it fondly. He made a surprised face and opened his arms wide, empty. He began crying again.

Nike said something to Krevel, and it sounded very definitive. “Let’s leave him,” probably. Krevel eyed his sobbing brother, hugging the invisible box, and nodded.

Nike took Krevel’s notebook out of his chest compartment, Krevel produced a pen. They sat down on the ground next to Nehmen. Nike put the pen to his lips in thought. Then, he drew a square on a fresh page.

“Box,” he said, tapping it with the pen. He wrote “BOX” next to it. Then he beckoned to Nehmen. The boy scowled at him. He wasn’t going to start learning English again! Never, never! Nike rolled his eyes. He pointed at Nehmen and said something that was definitely gibberish even in the common tongue. He tapped the square again and looked at Nehmen quizzically.

Nehmen blinked once, twice. Warmth blossomed in his chest. “Kastel,” he said.

“Kastel?” Krevel repeated.

“Kastel,” Nike nodded.

“Kastel,” Nehmen corrected them, took the pen from Nike and wrote: Kastel. He hesitated, and then ventured: “Box?”

“Box,” Nike nodded resolutely. “Kastel – box.”

It went on for weeks. At first Nehmen was ashamed that he never remembered much from the previous lesson. But really, neither did Nike. Nehmen could tell that he was fumbling just like him, and it was reassuring. They always revised what they had learned in the previous five days, and although it was draining and took up half the time of their lesson, Nehmen found that by the fifth day he knew nearly all of the words they revised.

He began looking forward to the lessons, inspired by Nike’s enthusiasm. The hoophead was no better at learning languages than him, but by all of Quater’s sons, did he have a drive. He had already managed to explain to Nehmen: he and Krevel would learn German, and in turn Nehmen would learn English. And Nike wasn’t backing out of the deal if it was raining weasels, he was utterly determined to learn that strange language, for no smaller reason than that it was fair.

“Es ist fair,” Nehmen nodded his head, and scribbled the three of them and their notebook into the notebook: “fair – fair”.

Sometimes Hoodians would want to intrude on their lessons, but the two brothers sent them away. Perhaps they were also self-conscious, Nehmen thought. But one day, Krevel did bring someone.

Klaymen watched their lesson quietly for a while, listening as they revised the previous five days. When they began coming up with new words to draw into the notebook, he joined in.

“Traum?” Klaymen said tentatively, watching Nehmen’s reaction. The German shook his head. “Traum. Trrraum.”

Krevel turned to the newbie and said one or two sentences to him, demonstrating the difference between the German “r” and the English “r”. Klaymen nodded his head. “Traum,” he said, trying to imitate the sound. “Traum. Dream.”

“Gut,” Nehmen beamed at him. He caught himself and switched the pronunciation. “Good.”

“Gut!” Nike affirmed and laughed.

When the lesson ended, Klaymen lingered, and so did everybody else. Nehmen looked around in confusion. Klaymen and Krevel exchanged glances.

“What’s going on?” Nike asked. His brow furrowed as he thought, and then he delivered the translation with a proud smile. “Was ist los?”

Klaymen said something. Krevel replied. Klaymen said something and nodded to Nehmen, which made the guy suddenly nervous. Krevel was silent for a while, looking at his hands. Then he met Nehmen’s eyes and said: “Es ist fair.”

Klaymen shrugged and smiled. He opened his chest compartment and he pulled out… the box.

It was smaller than it used to be, a different colour, too. But Nehmen recognised the intimate design, the wheels for tuning the language, the speaking hole. He grew tense with anticipation.

Klaymen passed the box to him, and Nehmen took it like a holy relic. It was smaller, it would fit into his chest compartment now. He checked the wheels: it was off. He tucked it inside his chest.

“Thank you,” he said, aware that his “th” was still terrible, and he hugged Klaymen. Behind his back, his brothers exchanged long looks.

Nehmen frolicked to the Entrance Room, intent on having some peace and quiet while he tuned the box. He repeated “Hoborg is the king” in English until the box said “Hoborg is der König”. Then he sat on the turn-and-turn stool and stared at it in thought.

Something in his gut felt amiss. He should be happy, right? Why was he sad instead? Why did he feel like something precious was slipping through his fingers?

Self-reflection was something that Nehmen didn’t like to do. It was so much easier to glide through his life without wondering whether his actions were right or wrong. He just did what he felt like, and he never regretted what he had done for a long time. Things could be fixed and people forgave. The question of right and wrong could be left to Nike, he was always there if Nehmen needed advice.

Nehmen stared at the box and he felt that he needed Nike’s advice. This wasn’t what he thought it would be. Nike would know what was wrong, surely.

In the end, though, things turned out differently. In the Explosive Shack Nehmen ran into some of his friends, who were ecstatic to see the return of the box.

“We missed you!” they shouted while the box did its best to keep up. “You were always gone. Were you embarrassed that you couldn’t understand us? Oh, but the party isn’t the same without you. Please, come with us.”

This melted Nehmen’s heart. He was wanted here. He had friends here. Nike could wait.

They played a game, and it was just like the old times. They told stories and Nehmen only caught half of it, and it was just like the old times. Nehmen spoke and the habit of leaving space for the box to fill came back to him naturally, just like the old times.

They partied until the evening. Before midnight they bade each other good night. Nehmen found one of his favourite cozy spots between the swirls of the Purple Tunnel, and fell swiftly asleep.

He dreamt of the box.

He remembered some of his dreams. Falling into the box. Being chased by the box. Being eaten, devoured by the box. Chaotic, and frightening.

He hugged himself. It was early in the morning, so early that birds had not even started singing yet. The air was crisp, and it felt cold. The box was sitting next to him, quietly, innocently. Ready to start speaking.

Nehmen turned it off, gathered it under his arm and began strolling through the Neverhood. Nothing moved, save for him. Not even Tao was at the fountain. She got up with the birds…

Nehmen found himself in front of the Castle. He set the box down on the ground and he sat cross-legged before it.

He took it into his hands, admiring the fine craft. The ivory wheels, the slim violet body. The deep, deep speaking hole.

He gulped. He checked if the box was on. It was off. Good.

Nehmen stared at his helpful, fine box. He stared at it, and remembered.

He remembered the time he had first got it. What a relief it had been to entirely abandon the notion that he would have to learn a foreign language. He remembered getting annoyed with its translating speed, with its even voice that delivered no emotion. He remembered convincing himself that it was fine, until he believed that it was fine.

I was wrong, a voice said in Nehmen’s head. He listened to it quietly. It was time to listen now.

He had been wrong to think that it could last forever. He had closed his eyes before the truth. Learning the common tongue was the only sensible thing to do. Even his brothers spoke the common tongue! How could he have been satisfied with telling them only half of what he meant, and understanding only half of what they meant?

Nehmen listened to his conscience longer, a rare moment of clarity. He had given up on learning. How could he have done that? How could he have sent Krevel away? His brother was trying to help so hard, maybe – yes, Nehmen realised, he had definitely been considering learning German for a while, that was why he didn’t refuse Nehmen’s half-joking offer, back in the Entrance Room. But he didn’t accept it either, because then… then Nehmen would never learn the common tongue. He would never speak the same language as them.

The boy rubbed his forehead. He should have treated Krevel better. And he shouldn’t have thought…

His gaze locked on the box. He shouldn’t have thought that that thing would save him. It was a thing, nothing more. It didn’t love him back as he loved it. It was an object, it was a device, it was a mean to an end, it wasn’t his saviour, it wasn’t his hope. He glared at it angrily. It stood between him and people. Reducing what they said to a string of unemotional words, reducing what he said to the same. It wasn’t a bridge, it stood in the way. It had always stood in the way between him and people, and Nehmen didn’t need the box, he needed the people. He needed his brothers, he needed their smiles and their kind voices, and not the dead and monotone voice of the box.

He couldn’t bear staying still anymore. He got to his feet and began pacing, circling to and fro and around the box, glaring at it, judging it.

“What have you ever done for me?” he lashed out. “I thought I wanted you, needed you. I thought you helped me. But you are cold, and unfeeling, and… and I don’t need you!” He stomped his foot, raising his voice at the silent box. “I don’t need your translations, they suck anyway! You’ve just held me back! I could have…” he swallowed a welling sob, “I could have learned English ages ago, if it wasn’t for you! I could have known what that poem by Hoborg said, I could have understood everything at that recital and instead I looked like an idiot because they forbid me from bringing you along ‘cause you’d disturb! You-” he pointed his finger at the box, “you suck! Yeah, you do! I- I don’t need you! I don’t need you!”

He thought back on the first lesson with his brothers, on the word that he learned. “Brauchen – need.” And in English, “du” was “you” and it wasn’t declinated.

“I need you not,” Nehmen said, unsure. He repeated it, louder. “I need you not. I need you not!” He circled the box like a lion. “I need you not! I. Need. You. Not!!” He kicked the box.

He froze. Frightened, he eyed the box.

Then he laughed. “I need you… not!” he cried out and stomped on the box. It was harder than he thought, sturdy, but he was in a rage. He tore off the buttons. He impaled the speaking hole on a spike of the Castle Bridge. He stomped on it, and kicked it, and punched it. He hated it. He hated it for everything it had taken away from him.

The box was little more than a scattered pile of cogwheels and junk when Nehmen finally noticed that someone was watching him from the Castle gate. He startled badly. It was Klaymen.

Nehmen looked around in panic. He had broken what Klaymen had lent him! Maybe it could still be put together, maybe Jerry-O could…

Klaymen stopped him from frantically gathering the junk by placing a hand on his shoulder. He spoke slowly, choosing his words carefully so that Nehmen would understand.

“It is okay.” He gave the boy an encouraging smile. “The box… bad for you. Drug. You need it… before.” He made a winding gesture with his hands. “Back. But now… no. You don’t need the box. No need. You learn English. You learn good. With brothers.”

Nehmen blinked back tears. He walked over to the edge of the bridge and Klaymen followed him. They stood side by side, peeking down into the darkness.

Nehmen’s arms twitched several times before they obeyed him and threw the remnants of the box into the void.

Klaymen helped him clean up the rest of the wreckage. They threw it all off the Neverhood. Maybe, Nehmen wondered, one day it would fall on Jerry-O’s head. What would the Skullmonkey think?

He stood on the edge of the bridge, he felt cold, and around him the Neverhood was beginning to wake up. He wandered… “without the box, I am air to them”…

Klaymen’s hand on his upper arm stopped that line of thought. The oldest Hoodian turned Nehmen to face him and gave him a heartfelt hug.

“You are good,” he announced to Nehmen, and it was so wonderful to be able to feel all the depth and love of an older brother in it. It was wonderful to understand. “You are brave.”

Nehmen did not know what “brave” meant. But he was determined to ask his brothers later.

And so I conclude my three stories about the three brothers: Krevel, Nike, and Nehmen. A story about hope, a story about pain, and a story about valour. They came to the Neverhood in the year 71 and they lived there for many centuries. These centuries changed them, as they changed the Neverhood by their presence.

May we never forget them.

![]()

![]()

![]()